Tales from Dystopia VII: Amazing grace

This is quite a long story, and I don’t know if it will fit in, or it may get very long. It covers a year we spent in Utrecht, and the ups and downs of living in Dystopia. It was a great time of learning for us, learning to depend on God, and learning that God uses unexpected people to make light shine in unexpected places.

Utrecht, in the Anglican Diocese of Zululand, had not had a priest for 30 years, and the Bishop of Zululand asked us to go there. We agreed. A priest used to come from Khambula, 70 kilometres away, to hold services once a month. He was Fr Edmund Xulu. He had two services, an English one in St Michael’s Church in the main street, Voor Street, and a Zulu one at St Matthias about a kilometre away in Generaal Street. St Michael’s was a small beautiful stone church, built in 1899, with a very impressive (and recent) stained-glass window. St Matthias was bigger, but built of bricks and mud plaster, with a corrugated iron roof. A stone in the wall said it was rebuilt in 1911.

We arrived in Utrecht in October 1976, and the following month 90% of the congregation of St Matthias vanished. They were ethnically cleansed, as was common under the apartheid policy. Utrecht black location was demolished, and the people moved to Osizweni, across the Buffalo River, out of the Diocese of Zululand, into the Diocese of Natal. We just had time to try to make contact with the priest at Madadeni (Duckponds) and Osizweni (Mountain), Fr Ariel Mothibi, to tell him about the people coming into his parish. Some members of their parish council came to a service at St Matthias, which was Fr Edmund Xulu’s farewell to the parish, and our welcome service, and farewell to the congregation. Within 3 weeks, most of them had gone. Madadeni and Osizweni were dumping grounds for people who had been ethically cleansed from what the government called “blackspots” all over northern Natal, but Fr Ariel Mothibi said I was the first priest who had ever told him that people would be coming there. The church passed all sorts of resolutions at synods condemning population removals, but made little provision for the pastoral care of the people who were moved.

There were some strange things about the two churches — St Matthias was at the far end of town from the black location, the old coloured location (Kak Straat) and the New Coloured Location (White City), and the people had to walk past St Michael’s on their way to St Matthias. With most of the congregation gone, St Matthias fell into disrepair, and the people were few enough to fit into St Michael’s, so we said that instead of having an English service at St Michael’s followed by a Zulu one at St Matthias once a month, we would have a bilingual one at St Michael’s every Sunday.

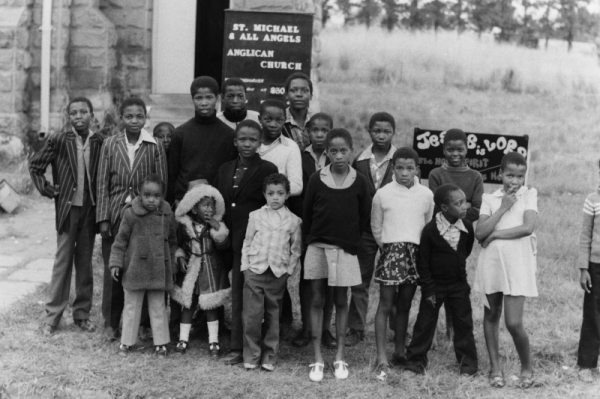

At St Michael’s there had been two services on Sunday mornings — the Methodists also used the the church twice a month. So there was an Anglican service at 8:30 and a Methodist one at 10:30. One of the coloured kids, Tyrone Dauman, who was about 11 or 12 years old, really enjoyed church, and asked if he could stay for the Methodist service. I said that was OK, the more he prayed the better. But the white Methodists didn’t like it, and stopped using St Michaels. They started holding their services at the white reform school on the outskirts of town. There was a sign outside St Michael’s, announcing the Methodist services, which was now redundant and misleading, so we painted over it, and wrote “Jesus is Lord — the Holy Spirit ministers here” instead.

The Assemblies of God used the church as well, on Sunday afternoons at 5:00 pm. Piet Joubert used to come the 55 kilometres from Newcastle to lead it. We started having evening services, at 7:00 pm. Often we would be going in as the Assemblies of God people were coming out. They were mainly black and coloured. The coloureds had not been moved, and the blacks who were left in Utrecht were mainly working at the three coal mines that surrounded the town. Piet Joubert invited us to join them one Sunday evening, as he wanted to show a film, and needed to show it later when it got dark. It was a crummy film, called The burning hell, and I wanted to giggle the whole way through, but it had an amazing effect on some of the youth, and that was the start of our youth group, led by Gloria Motaung and Sarah Oliphant. After the film we decided to have an informal ecumenical evangelistic Sunday evening service for all comers.

It was an amazing mixture for a small country town in the middle of the apartheid era. There was the Dutch Reformed Church, large and beautiful, attended by rich white farmers. I went a couple of times, before we started having our own evening services. They had about 20 people. But their morning services were well attended. And we had the rest, mostly the poor, black and coloured.

People sometimes think that apartheid was caused by “the Afrikaners”, and blame them for it. Well the National Party, which invented apartheid, certainly claimed to represent true Afrikaners, but not all Afrikaners thought that the National Party represented them. Piet Joubert, of the Assemblies of God, was an Afrikaner. He was a photographer in Newcastle, and he came over to Utrecht on Sunday evenings to minister to poor black and coloured people. When our services were fully ecumenical, our landlord used to come sometimes. He was a member of the Nederduitch Hervormde Kerk (the most right-wing of the Afrikaans Reformed sister churches), but their nearest congregation was also in Newcastle. He went there sometimes on Sunday mornings, but he came to our mixed services on Sunday evenings.

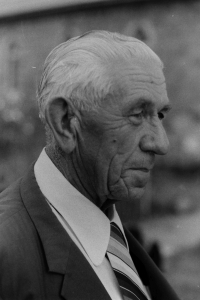

Another regular attender was Oom Manie Craffert, a member of the Afrikaans Baptist Church. He used to travel to Newcastle on Sunday mornings for services, and their minister came to Utrecht on Thursday evenings for Bible studies, but Oom Manie, who was an Afrikaner of Afrikaners, came to our mixed ecumenical services as well.

Piet Joubert once told in a sermon that he had taken a picture of a black man with an interesting face, and he had entered it in a competition and it had won a prize, so he put it on display in his shop window in Newcastle. One day a white woman passing in the street spat on his shop window, and so he went out and asked her why she had done so. She said he ought to be ashamed of himself, putting a picture of a horrible ugly thing like that with all the white brides. He asked her if she was a Christian, and she said she went to church, so he said, “That picture is not a horrible ugly thing. It is the image of God, and there will be no apartheid in heaven, and there will be none in hell either, and when you get there you will have to stew in all the hatred you had here, only far worse”, and she stalked off muttering to herself.

Another white Afrikaner who came was Oom Djoep Joubert. He was old and he was poor and he lived all alone with his dogs. His family did not care about him, and one day he did not show up for the service and so Piet Joubert and I went to his house to see what had happened, and found he had died. The dogs would not let us near to get his body out, and in the end the police had to shoot them. The church was his only family, and it was this mixed family that buried him, with no understakers because he had no money. But we gave him a good send off, better than that of many rich people, with his church family gathered round his grave.

We arranged a couple of evangelistic missions in the year we were there. There was a good response from the black people on the mines, and from the coloured people in Kak Straat, but not from the whites. Oom Manie Craffert said, “If you want the white heathen in this town to hear the Gospel, we must pray for the dominee (the Dutch Reformed minister), because they all go to his church.”

And the dominee, Frik Jordaan, tried, but he had an uphill battle. He had arrived in Utrecht about the same time as we did, and he said it had been a dominee’s church for too long, and now the congregation needed to become active. He sometimes also came to our Sunday evening services, and I think he found it a welcome break.

There was a young English-speaking white couple who became active as well. They were Neville and Lesley Richardson, who had recently arrived from the Witwatersrand. He was personnel manager for two of the mines, which belonged to the same company. He played a guitar to accompany some of our singing.

After one of our evangelistic outreaches we were joined by a Mocambique refugee, Alfredo Tembe. He was walking down the street, heard singing in the church, and came in. He had been a Frelimo soldier, and had fought in the war for the independence of Mocambique, but after the war his commanding officer found he was not at his post one day, so he was sacked from the army and came to South Africa, and worked on the mines as a carpenter. He sometimes came with me to some of our outlying congregations, and would give his testimony. He said he had learnt Zulu from reading the Zulu Bible and comparing it to the Portuguese.

There were several outlying congregations. After the Sunday morning service at Utrecht we would go out to one or other of them. Groenvlei was in a little hamlet, half way to Wakkerstroom, across the Transvaal (now Mpumalanga) border. Groenvlei consisted of the church, the police station, and a general store. The church was also used as a school. It was in the valley of the Slang (Snake) River, which wound and meandered over the valley with willows along its banks. At Christmas and Easter the church was decorated with greenery from the willow trees, wound around the rafters, and the window frames and everywhere else.Bengt Sundkler in his book Zulu Zion and some Swazi Zionists describes how the first Zionist baptisms took place in the Slang River. I wonder why they came over the hill from Wakkerstroom (where the Zionist movement started) to Grownvlei for their baptisms, or did the movement really start in Groenvlei?

There were two chapelwardens at Groenvlei, Jeremiah Sangweni and Enoch Zitha. One day we went to visit Sangweni, and found the place half demolished, with the thatch gone from the roofs. The neighbours said he was building a new house on a neighbouring farm, so we went over there. It was close to Zitha’s place, and Zitha came over. We read Morning Prayer together while they took a break from building, and the Psalm for the day had the verse “Ibusisiwe indoda emgodla wayo ugcwele bona: abayikujabha lapha bekhuluma nezitha zabo esangweni.” Psa 127:5 “Happy is the man that hath his quiver full of them: they shall not be ashamed, but they shall speak with the enemies in the gate.” In Zulu, Zitha means “enemies” and Sangweni means “at the gate”. I was reminded of a church I had seen a few years previously in Oxford, England, which had a sign outside saying “Rector: The Revd A.J.M. Saint. Churchwarden: Mrs K. Martyr.”

Soon after we arrived in Utrecht Groenvlei was host to the deanery conference, with representatives from all the congregations from Vryheid, Kambula, Paulpietersburg and elsewhere. It poured with rain, and we went in our old bakkie, inherited from Edmund Xulu when he left Khambula, slithering over the muddy roads, with out daughter Bridget who was born in Utrecht, and was just three weeks old. When we got to Groenvlei every member of the Mothers Union wanted to hold her, and change her nappy, which was probably too mcuh handling and she howled most of the time, and that made them want to change her nappy. And the generator on the bakkie died, so on the way back we had to push it up the hills. We tried to borrow a battery from one of the other cars, but it had different terminals and wouldn’t fit. Eventuallysomeone had to go back to Utrercht to get a battery, and I had to drive back in the dark and the mud with no lights.

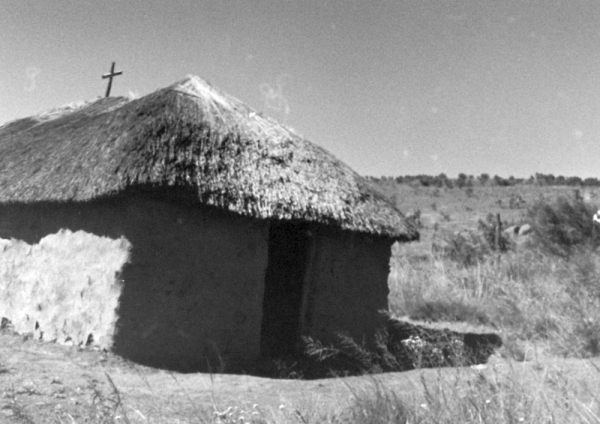

Another of the outlying congregations was Magidela. It was on a farm out in the country, and the leader of the congregation, Christina Ndebele, used to walk five miles with the altar linen on her head, and food for the congregation, and everything for the service. We had services there on Thursdays, because there weren’t enough Sundays in the month.

Alfredo Tembe came a couple of times, and gave his testimony, but his testimony sounded a little threadbare after a few times. Then one night he came to me, like Nicodemus. He had a confession to make.

The confession was to the effect that the Security Police (SB) had given him a tape recorder, to record my sermons and everything I said at meetings, and also anything said by Neville Richardson. This had troubled his conscience, and eventually he stopped taking the tape recorder around with him, and left it at the security office at the mine compound. But then the SB found there was something wrong with the tape recorder they had given him, and they could not play the tapes back on other machines. So they wanted the machine back to play the tapes. But the mine security officer had lent it to someone else, and it had disappeared. The SB told Alfredo that unless it was back the next day, he was in big trouble, and they would deport him back to Mocambique, and so he came to me with his story. They had also said that they would deport him back to Mocambique if he didn’t carry on spying for them. I took him to see Neville Richardson, to tell his story. It seemed that the SB had arranged with the mine compound manager that whenever Alfredo came out with me, the compound manager would sign his shift ticket to show he had worked (as a carpenter he did maintenance around the hostels). The compound manager was under Neville Richardson, the personnel manager, so in effect the compound manager was using the mine’s money to pay a junior employee to spy on his boss for the SB.

This had a sequel a few months later when some people from BOSS (the Bureau of State Security) visited the mine to enlist the cooperation of the management in maintaining security against subversion and so on, which later became known as the “total onslaught”. The mine management told them about Alfredo, and told BOSS to get lost. The men from BOSS said that that was the SB, and the SB were just dimwitted policemen, but BOSS were intelligent people from the intelligence arm of the government. The mine management was still reluctant to cooperate, and left BOSS cursing the SB. An instance of the left hand not lnowing what the right hand was doing, perhaps.

Another instance of the left hand not knowing what the right hand was doing was when I was visited by Bill Braithwaite, an Assemblies of God minister in Vryheid. He told me that he wanted to plant a church in Utrecht and that Paul Duffett, the Anglican priest in Vryheid had suggested that he come and talk to me. It appeared that he was holding Bible studies in Manie Craffert’s house, on occasions that the Afrikaans Baptist minister didn’t come through from Newcastle, and he regarded that as the nucleus of the church that he was “planting”. Oh well, Paul sows, and Apollos waters, but God gives the increase. I asked him if he knew that Piet Joubert, of the Assemblies of God in Newcastle, came over every Sunday evening. He didn’t. I found myself arranging an ecumenical encounter between the Assemblies of God in Vryheid and the Assemblies of God in Newcastle, which seemed very strange for an Anglican, as I then was, to be doing. But it seemed that Bill Braithwaite, like the Methodists, was thinking in terms of an all-white church. I later discovered that there were different branches of the Assemblies of God. There were the Coastal Assemblies, who were rather rigid and uptight and puritanical, and there were the inland Assemblies (I don’t know if they called themselves that, but they weren’t the “Coastal” ones) who were more laid back. One of the latter group, Bill Winter, stayed with us a few years later in Melmoth, during a mission. While he was with us we drank more wine in a fortnight than we normally did in a year. Bill said that the Coastal Assemblies would disapprove, “We call them our Brothers in Law.”

One day I went to take a service at Magidela, accompanied by a friend, Cyprian Mnwango, from Melmoth. We were about to start the service when a white man appeared at the door, carrying a rifle, and peremptorily demanded that the church be closed. He said it was his farm, and he didn’t want the church there any more. It turned out that he was an absentee landlord, a Mr Klingenberg, who lived on another farm at Commondale, near Piet Retief. I asked him why he had allowed the church to be built there in the first place, but he said it had been there when he had come to the place, and it had nothing to do with him. He went away, and looked frightened.

When he had gone Mrs Ndebele said that he had encouraged them to build the church about 12 years previously, and had encouraged the Mbuli family to move near the church to look after it. He had been opposed to the Zionists because he said they stole his cattle, so I thought he might be thinking the Anglicans were stealing his cattle.

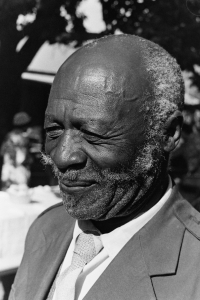

After the last service at Magidela. On the left is Christina Ndebele, who carried the altar linen from her home. The ploughshare hanging from a pole served as a church bell.

We went ahead and had the service anyway. As we were leaving, driving through the fields to the road, there was a big roundup of cattle going on, and there was a policeman there who said his name was Eric Dlomo. He said that the farmer had complained that some of his cattle had been stolen. A little further on we saw the farmer again, still with his gun, with a neighbour, Mr Kemp, so I went to ask him if he had closed the church because he thought the church people were stealing his cattle, or if they had offended him in any other way,

but he just said “bugger off”, and his neighbour, Mr Kemp, was equally rude and unreasonable. There were several white plain-clothes police around, but they looked really thuggish, and more like cattle rustlers than policemen. I then thought of Alfredo, and wondered if the police were putting pressure on Mr Klingenberg to close the church.

Another of our outlying congregations was Enzimane. There was a farm school there, which used the church building, and I discovered that I was expected to be the school manager. Most of the outlying churches were used as schools during the week. Mrs Saulina Sithole, the teacher at Enzimane had not been paid for six months. She had passed retirement age, but carried on teaching because there was no one to replace her, but that meant she had to be reappointed each year, and it took the bureaucrats in Pretoria about nine months to realise that and to actually pay her her salary. In the mean time she had to live on credit from the local shopkeepers, who fortunately knew that she was an honest woman, and supplied her with groceries on credit.

The Bantu Education circuit inspector came from Glencoe to explain the system of farm schools. Twenty years previously the government had nationalised the church schools. In districts like Utrecht, where most of the land was white-owned farms, the church had run the schools in church buildings, and they were attended mainly by children of farm labourers (as were the church services). Government policy was that these schools in churches should be phased out. Each farm should have its own school, and the farmers should build and manage the schools for their labourers. It was in their own interest, because if there were no schools, it would be difficult to keep workers with children of school-going age. But most farmers weren’t interested in education for their labourers’ children, and it was simpler to register the former church schools as farm schools, and let the clergy manage them. So the government nationalised church schools, and the clergy ended up as unpaid administrators working for the government. And along comes a girl who has just passed grade 7, applying for a job as a teacher, teaching Grades I and II. But that didn’t matter, because, as Dr Verwoerd said, when introducing the Bantu Education Bill in Parliament, “The school must equip him (the native) to meet the demands which the economic life of South Africa will impose upon him… there is no place for the native in European society above the level of certain forms of labour.”[1] So Bantu Education was to be education for servitude, and the children of farm labourers only needed enough education to enable them to work as farm labourers when they grew up. So when Mrs Sithole did finally retire, she would probably be replaced by a kid with a Grade 7 or 8 education.

While we were in Utrecht we sometimes went to Paulpietersburg for clergy meetings and deanery conferences. My grandfather had died there 30 years before, and at the time I was staying with my mother at Ingogo. We went across for the funeral, and that was the first time I had been to Utrecht, and had a few memories of it — the view of the town from Knights Hill at sunset as we were returning. So when we lived at Utrecht, on one visit to Paulpietersburg we went to the town hall and looked at the cemetery register to find my grandfather’s gave. It was unmarked, but we could tell where it was from the adjacent graves. It was 28 years before, and seemed like the remote past. We tried to discover some of the history of Utrecht parish in that period, when there was a priest living there. Where did he live? Who went to the church? Nobody knew. It was too long ago. The two white families that belonged to the church when we were. the Lewarnes and the Nichols, there worked on the mines. They were transferred there and would be transferred away. The black families had been forcibly removed. The parish registers had names of people baptised, married and buried, but who they were and what they did was unknown. Nobody could tell us where the priest lived. And now, the time we were there is even longer ago that that time was. So I write this down in case anyone else wonders what things were like in the olden days, as I wondered when I was living in what are now the olden days.

We were in Utrecht for just under a year, from October 1976 to September 1977. We saw racism. We saw poverty. We saw ethnic cleansing. We saw a church closed at gunpoint. We got a clearer insight into the working of the system of SB informers. We saw the lunacy of Bantu Education. It was definitely dystopia.

But we also saw, by the amazing grace of God, things that transcended dystopia and gave a glimpses of heaven on earth. We met people like Saulina Sithole, who was poor and had a tough life as a widow, but was a dedicated teacher and carried on teaching as well as she could even though she hadn’t been paid. We met people like Christina Ndebele, who walked five miles to church carrying the church linen on her head, and who was chased out at gunpoint, but was always smiling and cheerful and laughing, no matter what happened. Her happiness and joy were infections, and she made other people happy. We met people like Piet Joubert, who preached against racism and believed in a God who gives dignity to the poor and oppressed, and wasn’t afraid to say so.

Even today one hears phrases like “our people” and “own people”. A poster I saw a couple of years ago said “eie volk, eie land” (own people, own land). And no, it wasn’t (consciously) promoting the idea of agrarian slavery. It was expressing the common assumption that “our” people are those who share the same skin colour as us, the same language, the same culture. But for the people who came to the Sunday evening services in Utrecht, “our” people were God’s people.

And so on Sunday evenings in the little stone church at Utrecht we saw people gathering together, people that society and the government said could not and should not gather, white and black, Afrikaans and English and Zulu, and mostly the poor and despised of the world, to celebrate a homeland that is to come. Not a homeland that the world offered, a place one’s ancestors had putatively come from[2], but a deposit, an arrabon, of a new South Africa, a new heaven, a new earth.

And so we used to sing:

Sing’ abahambayo thina kulomhlaba

Khepa siyekhaya ezulwini

Sithi Aleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

We are pilgrims in this world

But we have a home in heaven

Saying Alleluiia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

And it wasn’t mere escapism, because on those Sunday evenings God gave us a glimpse of heaven on earth.

_____

Notes and references

[1] Huddleston, Trevor. 1957. Naught for your comfort. London: Fontana. p. 119.

[2] The apartheid policy said that black people in South Africa could only have political rights in “homelands”, and was based on the idea that in some remote past their ancestors had come from somewhere else to the “white” areas and that everyone must eventually go back to these homelands — hence the removal of people from the Utrecht location to “Mountain”, as the people called it. But the ancestors of the farm labourers in the Utrecht district had lived there long before the white farmers came. What happened was that a group of filibusters from the Transvaal arranged to help King Mpande of Zululand in one of his wars. And when the war was over they stated their price, which was almost half his kingdom. And so they took over the districts of Utrecht, Vryheid and Babanango to form the New Republic, with Vryheid as its capital. Eventually the New Republic joined the South African Republic (Transvaal) , but after the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 its territory was annexed by Natal, which had already annexed the rest of Zululand ten years previously.