After Mandela, what?

The death of Nelson Mandela has prompted many attempts to assess and evaluate his life and works and achievements. On the day following his death my Facebook status/wall/timeline or whatever they call it now was filled with tributes from people around the world. Most were positive, especially those from South Africans.

The few negative responses I saw were mostly from American libertarians, which I think says more about American libertarians than it does about Nelson Mandela.

Some conspiracy theorists and malicious persons did their best to predict pogroms after his death, as described in this article Helter Skelter In South Africa? Alarmists Spread Fear That Whites Will Be Massacred After Nelson Mandela Dies.

But apart from American libertarians and the loony right (like this idiot, who compared Mandela with Adolf Hitler, Joe Stalin, and Pol Pot) most people emphasised his positive achievements. Yes, the media tended to be hagiographical and uncritical, so that some suggested that they airbrushed his failings. But most of those who complained along these lines indicated as the “truth” the right-wing media that vilified him. There was a difference, though. The hagiographical articles can at least report things he actually said, even if somewhat selectively. In the time that the right-wing media vilified him, he could not be quoted, and the picture of him was coloured by the paranoia of the Security Police, who are also quoted in one of the more balanced articles of this type, here: Nelson Mandela: he was never simply the benign old man – Telegraph

But if we are thinking about what happens after Mandela, we already know. He retired as President and leader of the ANC nearly 15 years ago. We have seen what has happened. As my fellow blogger Macrina Walker puts it:

I suspect that one of the reasons many of us are so saddened at Madiba’s passing is that he was the last of a generation and represents an ideal that all-too-often appears to be crumbling. However much lip service people pay to a life of sacrifice and integrity, the reality is that such ideals are quickly undermined by the temptations of self-enrichment and easy pleasure. A virtuous life has never been easy, but it often seems as if we live in a world in which it is becoming more difficult.

via A Good Life: Saint Nicholas, Saint Anthony and Madiba | A vow of conversation.

The last of a generation

As someone pointed out on Twitter, three great trees fell at ten year intervals: Oliver Tambo in 1993, Walter Sisulu in 2003, and Nelson Mandela in 2013.

One is tempted to think that we will not see their like again.

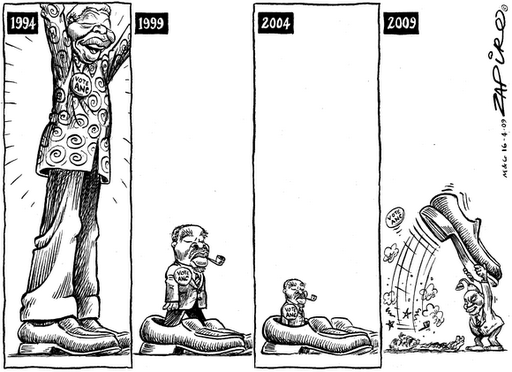

As Zapiro put it in a cartoon in 2009:

Thabo Mbeki, for all his failings, was vastly better than some of his contemporaries, notably Tony Blair and George Bush.

But if we want to assess Nelson Mandela’s legacy, we need to look at the decade from 1989-1999.

1989 was the Annus Mirabilis, the wonderful year in which freedom was breaking out all over, and dictators fell in many countries, including South Africa. The seeds were sown a bit earlier when Mikhail Gorbachev in the USSR introduced policies of glasnost and perestroika, and in South Africa, with the fall of PW Botha in 1989, there was talk of Pretoriastroika. The release of Nelson Mandela and the unbanning of the ANC (and other opposition parties) in February 1990 opened the way for a new democratic era in South African politics.

There were bad things in that time too. There was a lot of political violence, and much of it was provoked by the so-called “Third Force”. Perhaps historians will eventually establish more clearly the nature of that violence, and the nature of the “Third Force”, but I don’t want to talk about that now.

My main memory of that period was that the ANC, in particular, seemed to be taking one of their own slogans seriously — that “the people shall govern”. A lot of energy and effort was put into soliciting public opinion and ideas on all kinds of things, from the content of the constitution to the promotion of education, art and culture. Conferences were held, submissions sought, and many of these things were subsequently incorporated into the constitution.

There was a feeling of “inclusiveness” in the best sense. If there were to be leaders, the leaders must be sensitive to the needs of the people, and must listen to the people. There was a Zulu proverb, that a chief is a chief because of the people. So there was a ferment of ideas, and a feeling that anything was possible.

This inclusiveness of was not the ideological western kind, but part of the African idea of ubuntu.

I had sometimes been at church synods that had been run along the lines of Western parliaments, where a motion was proposed and seconded and debated and amended and eventually a vote was taken, and the Ayes or the Noes had it. But sometimes black members of synod complained that this adversarial procedure was not in accord with African culture, where the matter was discussed until consensus was reached. And I saw this in a somewhat different setting, in the Anglican diocese of Zululand, where it happened. People would discuss something, and perhaps have different viewpoints, but when it had been thrashed out the bishop would sum up, and announce the decision. But it was not his decision alone, but that of the meeting. He was the voice of the people.

The first democratic election in South Africa was inclusive. There were no areas in which people were registered to vote. You could vote anywhere, and as long as you could prove that you were who you were, you could vote. There was the same spirit of inclusiveness in the Government of National Unity (GNU) that followed. Inkatha had threatened to boycott the election until the last minute, and as a result of their intransigence 700 people died. In the end they not only participated in the election, but in the GNU that followed. There was a deliberate effort to include them.

The only holdout was the Democratic Party, which was based on white culture, and wanted to be an opposition, and therefore to oppose everything the government of National Unity did, good or bad, because the job of an opposition was to oppose and therefore to oppose everything on principle. That was part of the adversarial principle of law and politics, the “Westminster system” that South Africa had inherited from the British Empire.

The Annus Mirablilis of 1989 therefore marked the beginning of a miraculous decade of freedom in South Africa. Whether it did the same in Romania, Hungary, Poland, Russia, Ukraine, Azerbajan and other countries that had been freed from dictatorship at the same time, I don’t know. But in South Africa it was a good time to be alive, to savour new-found freedom, a time of seemingly limitless possibilities.

And Nelson Mandela was the one at the helm during this time, and so became the symbol, the “icon” (as the media would have it) of our new-found freedom.

But such things never last. There is always the worm in the apple.

The 19th-century liberal historian, Lord Acton, once famously said that all power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Between 1990 and 1994 the ANC was not in power. It had no patronage, and so could freely promote the free flow of ideas. It encouraged the people to speak, and it listened to what the people said. Some people, so inured to the oppressive rule of the past, were still afraid to speak. Some, so brainwashed by National Party propaganda, were incapable of hearing the ANC’s invitation to speak. Some, like the dwarfs in CS Lewis’s story The last battle, were still convinced that they were in a dark stable theatened by a monster, and not in the open air of freedom. But some people did speak, and the ANC listened.

But all power tends to corrupt, and after 1994 the ANC had power. Certain people began to see that if they could get themselves elected to the committee of the local ANC branch, they could influence the choice of candidates for local government elections or provincial elections, and thus influence the people who controlled the budget, and so the tenderpreneur was born.

Some people in the ANC still listened to the voice of the people, or tried to, but for an increasing number the voice of money grew louder and louder, and drowned out the voice of the people.

Thabo Mbeki was aware of this, and he warned about it in his address to the 52nd National Conference of the ANC at Polokwane in December 2007. But he wasn’t even preaching to the choir, because by then most of the choristers were there because they had money, and not because they could sing.

But I don’t think of that as Mandela’s legacy. Mandela’s legacy was that miraculous decade of 1989 to 1999, when anything seemed possible. And perhaps there are still some people around who caught the vision, and will pass it on to others, who may, sometime, work to realise it.

And in the mean time, we sing, with Parchment:

Yesterday’s dream didn’t quite come true

We fought for our freedom, and what did it do?

Now no one can see where they stand.

So let there be light in the land,

Let there be light in the people

Let there be God in our lives fromj now on.

Communist regimes always descend into kleptomania and corruption before their eventual collapse. The ANC are no exception.