Tales from Dystopia XIV: Holy Cross, Onamunama

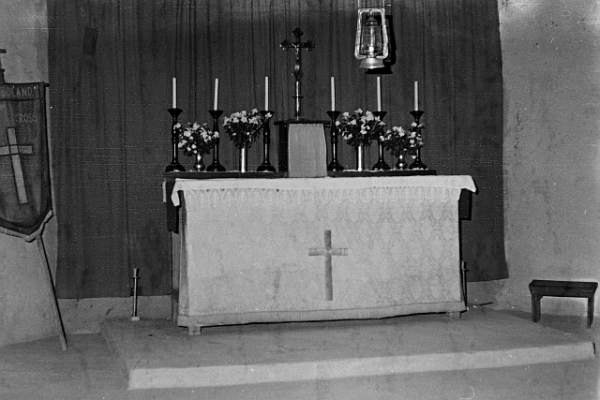

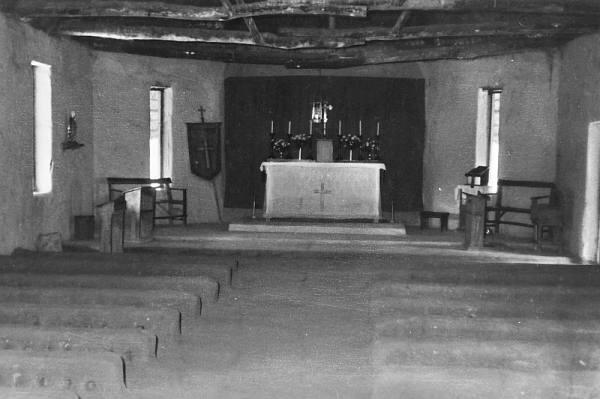

Last week we bought a negative scanner, and I’ve been scanning old photos, mainly from the 1969-1975 period, and among them were photos of the Anglican Church of Holy Cross at Onamunama in Ovamboland, Namibia.

It was a few miles east of Odibo, where the main Anglican centre in Ovamboland was, and in September 1971 I went to visit it with Fr Lazarus Haukongo, who was then the rector of the parish. Like most of the Anglican parishes in Uukwanyama, it was close to the Angolan border, and about half the parishioners came from the Angolan side of the border. I really appreciated the opportunity to visit it, because at that time the apartheid government was very reluctant to give outside church workers permits to go to Ovamboland, and withdrew the permits on the slightest pretext. I had no permit, and had sneaked into Ovamboland without a permit in rather sad circumstances — a bakkie bringing delegates home from the diocesan synod in Windhoek had rolled, and two had been killed, while several others were in hospital in Windhoek. Those less severly injured were stranded, so I brought them back in my bakkie — for more on this see here.

I knew about the parish of Holy Cross by reputation.

In the 1970s there was a contract labour system in Namibia, in which people in Ovamboland would be recruited to work in the south of Namibia in mines, farms and factories, usually as unskilled labourers. Ovamboland was at that time self-sufficient in food and barely had a cash economy. People did not have to work (in the sense of having “jobs”) in order to survive. They raised crops and cattle. They only needed cash for luxury items — manufactured goods like radios, bicycles, sewing machines etc. They were recruited by SWANLA, the South West Africa Native Labour Association, which was a kind of cartel run by the government and the bigger employers, which set the rates of pay, terms and periods of service, etc. SWANLA had a monopoly. No one in Ocamboland could get a job elsewhere except through SWANLA. People were not recruited on the basis of their skills or education. They were simply “labour units”.[1]

This meant that contract workers recruited from one place might often go to the same job, such as a mine or a factory. I was then based in Windhoek, and sometimes two or three of us would go to visit isolated mines to see if there were any church members there, and would hold a service, and offer them books for sale. Sometimes at the mines there could be groups of up to 20 people from the same parish, And if they were from the parish of Holy Cross, Onamunama, they did not wait for someone from the diocesan headquarters in Windhoek to visit them. They organised their own services. At one such mine the diocean treasurer was most impressed when they handed him six months worth of collections they had taken. It seemed that Fr Lazarus Haukongo had taught his parishioners well, and that they had not only heard about the ministry of the laity, but they took the initiative and practised it. Apart from anything else, after being a “labour unit” all week, it gave them an opportunity to be human on Sundays.

So I was very curious to see the home church of the active Christians I had met on mines in the south.

My visit was on a weekday, so there were not many people around. I went with Toni Halberstadt, who was then teaching at the high school at Odibo (soon afterwards her permit was withdrawn, and she, like me, was deported from Namibia in March 1972).

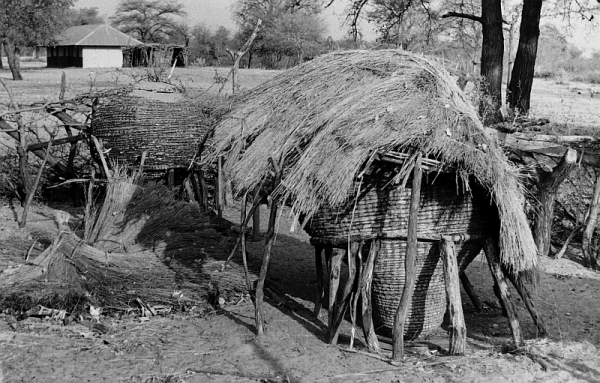

The church was built in harmony with the local style of domestic architecture, with a thatched roof, and Fr Lazarus took us to see a nearby home, built in the traditional style. I can’t remember now if it was his own home, or that of one of his parishioners.

As I have mentioned, the church was close to the Angolan border — about 200 metres, and many of the parishioners lived on the Angolan side. The border bisected Uukwanyama territory, and indeed bisected Owambo (the home of the Ovambo people) itself. About two-fifths of Owambo was north of the border, and three-fifths to the south. There was a road on either side of the border fence, a rough sandy track. A friend told me he had seen someone riding a bicycle down the road, , and when the road got bad on one side of the fence, he simply lifted the bike over the fence and continued riding on the other side.

On one occasion Fr Lazarus said he was visiting parishioners on the Angolan side of the border, and the Portuguese police stopped him and asked who he was and where he came from, and when he told them they said he must have a passport and must get it stamped at the border crossing at Odibo. He pointed at his clerical collar and said “This is my passport.”

Toni Halberstadt watches as Fr Lazarus Haukongo shows how a drum is used to tell people about church services

Within a very few years, all this was to change.

The South African army moved in to Ovamboland in force. They demolished most of the Anglican churches, and the homes of their parishioners, and forced them to move away from the border. For the next 15 years or so the people of Ovamboland experienced militqary rule. The parishioners living on the Angola side were altogether cut off from the church. Civilians could no longer move across the border to minister to them. The only people who moved freely across the border were South African soldiers, who went to kill them.

So the photos I took when I visited Holy Cross, Onamunama forty years ago show a past that was soon to vanish — back then nobody knew how soon.

Ovambo corn storage bin, Onamunama, September 1971. It is raised from the ground to protect the corn from insects, and covered with a thatched roof to protect it from rain and birds. Ovambo corn is nutritious, and at that time there was no malnutrition in Ovamboland, which was self-sufficient in food

For more about Ovamboland and Namibia in that period (1971), see Toni Halberstadt’s Namibia Scrapbook.

Tales from Dystopia is a series of posts I am doing at irregular intervals, with memories of the apartheid era. Some of my fellow South African bloggers said that we should not forget what happened in our past, so that we can learn the lessons of history. So these posts are my contribution to that.

Notes

[1] Labour Units. Seeing workers as “labour units” rather than as human beings was bad for employers as well as for employees, A worker who served an 18-month contract with one employer, and learnt something about the job, had no guarantee of going back to the same employer under a new contract. So employers usually got unskilled and inexperienced workers, and employees were never in a job long enough to develop their skills.

After seeing the effects of the contract labour system, and the strikes it gave rise to, I was horrified when, about 10 years later, I read an advertisement in a South African newspaper (the Sunday Times) for a “Human Resources manager”. The term seemed to indicate that the dehumanising approach of regarding employees as “labour units” was spreading.

Perhaps I was naive, but when I worked in the Editorial Department at the University of South Africa, we had staff meetings to allocate various responsibilities. At one such meeting one person was designated as the “HR person”. A few months later there was conflict in the department, and great hostility between a couple of members of staff. I suggested at a staff meeting that the matter be referred to that person. Everyone looked blank, and the director asked “Why her?” And I said, “Isn’t she the Human Relations person?” It turned out that she wasn’t. She was the Human Resources person, and the dehumanising “labour units” ideology had even infiltrated academia.

Great report and photo’s, Steve. One correction: I later found out that the Ovambo people DID need money for more than those consumer items, namely because the S.A. gov’t taxed them. So they were actually forced into the contract labour system.

And one P.S., that I learned from Tamina Hiyalwa, one of my Odibo students who I had the good fortune of being with in 2011. At that time, she was still grieving over the decimation of her home village : After those Onamunama homes were razed (to create the barren no-go-zone that the S.A. armed forces and their Koevoet hires patrolled, near the Angola border), they housed them further away from the border in horrible sterile concrete-block residences, like the ones in the “locations”, lined up in rows.

I gather that it destroyed much of their sense of community and crushed their spirit.

That’s what they were still living in in 2011.