Tales from Dystopia X: The banality of evil

The phrase “the banality of evil” became prominent with the publication of Hannah Arendt’s book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, on the trial of Adolph Eichmann in Jerusalem. Eichman, an administrator in the bureaucracy of Nazi death camps, thought that he was simply doing his job. The phrase “the banality of evil” describes the thesis that the great evils in history generally, and the Holocaust in particular, were not executed by fanatics or sociopaths, but rather by ordinary people who accepted the premises of their state and therefore participated with the view that their actions were normal.

But to me the concept behind the phrase is perhaps best illustrated by a passage from C.S. Lewis’s novel Perelandra where the protagonist, Ransom, is watching the activities of a mad scientist, Weston, in trying to spoil a world as yet uncorrupted by evil. Weston engages in acts of wanton cruelty and destruction, torturing small animals, and then calls Ransom’s name endlessly, and when Ransom replies, Weston says, “Nothing.”

[Ransom] taught imself to keep silent in the end; not that the torture of resisting his impulse to speak was less than the torture of response but because something with him rose up to combat the the tormentor’s assurance that he would yield in the end. If the attack had been of some more violent kind it might have been easier to resist. What chilled and almost cowed him was the union of malice with something nearly childish. For temptation, for blasphemy, for a whole battery of horrors, he was in some sort prepared, but hardly for this petty indefatigable nagging as of a nasty little boy at a preparatory school. Indeed no imagined horror could have surpassed the sense which grew within him as the slow hours passed, that this creature was, by all human standards, inside out — its heart on the surface and its shallowness at the heart. On the surface, great designs and an antagonism to Heaven which involved the fate of worlds: but deep within, when every veil had been pierced, was there, after all, nothing but a black puerility, an aimless empty spitefulness content to sate itself with the tiniest cruelties, as love does not disdain the smallest kindness?

Today is the fifth anniversary of this blog, which I started on 13 February 2007, when it seemed that Blogger was broken and would never be fixed. I thought I should write something to mark the occasion, and had just been writing elsewhere about events of 40 years ago, thought I would post them here too. “Elsewhere” is a mailing list where I communicate with people I worked with in the Anglican Church in Namibia, and have been posting extracts from my diary. And I think that those extracts from my diary can illustrate something of the banality of evil.

Extracts from diary of Stephen Hayes

These deal at some length with ministry to Anglicans in the Ovitoto Reserve in Namibia (then known as South West Africa) , and the lengths that government officials went to to try to prevent such ministry.

Friday 11 Feb 1972

Magdalena Bahuurua phoned up, and said her auntie had died, so I went out to see her, and arranged to go to Ovitoto to conduct the funeral. I took Lisa to the Alhambra to see “Bedknobs and broomsticks”, which was rather fun, though not a brilliant movie.[1]

Notes and hindsight

Aletta Tooromba lived in Ovitoto Reserve, about 90 miles from Windhoek via Ohahandja by road, though considerably closer as the crow flies. For the previous year, once I had got a reliable vehicle, I had been going there to take her communion, and the other Anglican members of the family also joined in the services. Because the Anglicans had neglected then (the last priest who had gone there was Fr Ron Gestwicki, who had been deported s couple of years before) many of the family members had joined other denominations, like the St John Apostolic Faith Church and the St Philip Apostolic Faith Church.

Security Police report to Secretary of Justice dated 17 Dec 1971:

Twice this year he entered the Ovitoto Reserve without a permit, though he was fully aware that he needed a permit.His application for a permit was repeatedly rejected. This open provocation of HAYES put the Department of Bantu Administration and Development in great difficulty especially after the Attorney-General of S.W.A refused to institute a prosecution after his first offence. During the student riots in the north of S.W.A. there were regular reports of HAYES involvement in the organisation and development of events.

In an earlier, but much longer memorandum (28 pages), item 117 reads as

follows:

21/6/1971: Hayes let Aitchison know that he was forbidden by the superintendent of the Ovitoto Reserve to enter the reserve. On 5/6/1971 he actually entered the reserve without a permit, and afterwards let the magistrate know by letter what he had done. The Attorney General later refused any prosecution, saying that Hayes was busy with provocation, and that the case was doubtful.

What actually happened was that Magdalena Bahuurua, the leader of the Herero Anglicans, who had formerly been Bishop Mize’s housekeeper, kept nagging me to take communion to her aunt, Aletta Tooromba, who was old and sickly and lived in Ovitoto.

I asked about this among the clergy of the diocese, and someone, I think George Pierce, advised me to write to the magistrate at Okahandja at ask for a permit. I did so, but heard nothing. Later I wrote a second letter, or perhaps the bishop wrote a second letter, but again there was no response, apart from a letter asking for proof that I was a minister, which was duly sent.

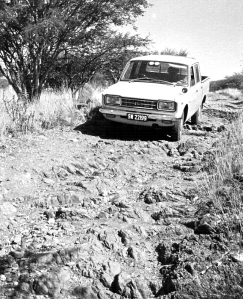

Magdalena, who was concerned that her aunt would die without receiving communion, kept urging me to go, so on one Saturday, having recently bought a new Daihatsu double-cab bakkie (which I named Strawberry, after the flying horse in C.S. Lewis’s The magicians nephew), I went. Here is my diary entry relating to that:

Saturday 16 January 1971

I celebrated Mass at the Cathedral in the morning, and then went to pick up Magdalena to go to the Ovitoto Reserve. She was not at home, so I went to Magdalena Kaune’s house, and she said they were only expecting to go tomorrow. I went to fetch Hiskia [2], and asked if he would like to come and interpret for me. He seemed quite pleased to come. By the time we had collected everyone and set off it was nearly 11:00 and we had ten people in all loaded in to Strawberry – seven in the cab and three on the back.

At Okahandja we turned off on to the Steinhausen road, and after going east for about twenty miles turned off into Ovitoto itself – and from there it was only a two wheel track, going over sand sometimes, and over rocks and bumps. Strawberry didn’t seem to mind at all. Ovitoto itself was quite beautiful. Some parts were bare and overgrazed, but everywhere there were green trees, and in some places green grass and yellow flowers. At one place Magdalena said everyone must get off, and I must cross the river, and pay my respects to the Superintendent of the Ovitoto Reserve, Mr Pretorius. So I drove down the muddy river bank, crossed a sand bank, and went to his house on the other side, only to find that he was not in.

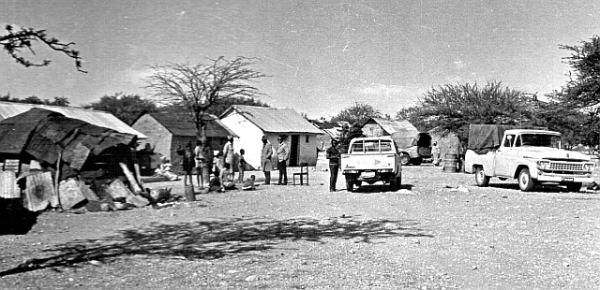

We continued on our way, stopping at the store a little further on for a drink of water. The road got worse and worse, and we drove about fifteen miles over the hills and across riverbeds, with Madalena encouragingly pointing out the places where Fr Gestwicki had got stuck in the Landrover – but Strawberry never faltered. Finally we arrived at Oruuua. We first went to see Magdalena’s family – her mother and sisters, and her sister’s son, Mateus, of the Oruuano Church, to whom her father had left the care of the congregation there.

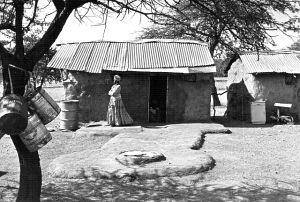

We then went down to her aunt’s place, a couple of hundred metres away, and there was the house where we were to hold the service, empty but for a couple of chairs and a table, and Madalena’s aunt, Aletta Tooromba, who could hardly walk. The floor had been newly plastered with cowdung, and there was a crucifix hanging on one wall. I arranged for Hiskia to read the Epistle, and Mateus to choose the hymns. I celebrated the Mass westward facing, in Herero, and Hiskia translated the sermon. It was about the best service I have ever been to in South West, because the congregation participated fully. There was no hesitation about the responses and they said practically all the service except the absolution and the canon. At the end we sang some of the Oruuano Church hymns, with clapping, and Magdalena walked out in disgust, but the rest of them all laughed at her, and in the end she came back laughing too. We then sang “Nkosi silelel’ iAfrika” in Zulu and Herero, and the congregation said they liked it.

We went back up to Magdalena’s mother’s place, and Hiskia and I drank omaere with Mateus and talked, and we left about half an hour later. The journey back to Windhoek was much the same as on the way out, except that we went into to Okahandja, and visited some of the Anglicans there, and I arranged with Margriet Jaantjies to have a service there next Sunday.

_____

The next time I tried to visit Ovitoto was on 27 March 1971 – diary entry

follows:

I fetched Magdalena Bahuurua, Magdalena Kaune and other Herero Anglicans from Katutura and we then went to Ovitoto. On the way we crossed the Swakop River, which was flooding in quite a rush on one side, and we had to go down a steep bank to splash through it. Then we passed fields full of purple flowers. When we reached the superintendent’s office, I went to see him, but he said he could not let me in without a permit. I explained to him that I had applied for one at the magistrate at Okahandja, and they had only asked for proof that I was a minister. He insisted that I needed a permit, so I went over to his office and wrote another application, and asked him to see that it was sent in. Then I collected the people who had waited at the other side of the river, and we went back to Okahandja. Magdalena Kaune was mad as a snake, and so were they all, because we had loaded up with great bags of mealie meal to give to her mother in Ovitoto.

We got back to Windhoek in the afternoon and Fr Frank phoned to say that Dick had left a message for him to ask him to tell us that Jenny Aitchison had phoned. It sounded bad, and we thought John might have been banned again.[3] We tried to phone the Smalls but got no reply, and later when we did tried to phone the Smalls but got no reply, and later when we did get through they said they had not seen the Aitchisons at all. We then tried the Richmonds, and spoke to Rose and John and Jenny were there, so we spoke to them. John said he had indeed been banned again, but he was not discouraged. He said the banning order was very similar to the last one, with a couple of new things added, such as not being allowed to write political letters. The government begins to seem the face of Satan incarnate, scattering the saints and making war on them.

(end of diary entry)

On the way back from the aborted trip to Ovitoto we sang a Herero chorus that seemed appropriate to the occasion:

Satana pita mondjira, matu tjaere okukumba

Matu hungire na Jsus, mukuru wokombanda(Satan get out of the road, he tries to keep us from praying

we pray to Jesus, the God of the heavenly hosts.)

Satan had certainly tried, through his agent Mr Pretorius, to keep us from praying with old Aletta Tooromba.

I had also noted the Administrator’s Proclamation which, according to Mr Pretorius, said that a permit was required to enter Ovitoto, and back in the Advertiser office on Monday (I worked as a proofreader with the local newspaper, the Windhoek Advertiser), where they had a copy of the Laws of South West Africa, I looked up the section that Mr Pretorius had referred to, and it said nothing whatever about needing a permit to enter the reserve. A permit was only needed if someone who was not already a resident wanted to “encamp or reside” there.

I concluded that Mr Pretorius was exceeding his authority in demanding a permit.

The next time I went was the visit recorded in the SB report above:

Saturday 5 Jun 1971

I woke at 7:15, and fetched Magdalena Bahuurua, and drove out to Ovitoto. We passed the superintendent’s office without incident, so I suppose he didn’t notice us. We drove on to Oruua. Magdalena’s brother was there, and several big shots from the St Philip Church, so most of those who attended our service were children, about 25 altogether, with four communicants. Everyone seemed busy afterwards, so we left almost immediately, but at least Aletta Tooromba had received communion.

We called in at Okahandja location to tell Margriet Jaantjies that the service would be late tomorrow, because I will be celebrating at the 9:30 Mass at the Cathedral. Margriet was out, however. I was half asleep driving back to Windhoek, and got back at 4:30. I went to the Diocesan Office and wrote a letter to the magistrate at Okahandja telling him I had been to Ovitoto without a permit. That way they can not accuse us of being underhand and subversive. Roger Ellick, the Methodist minister from Khomasdal, came in and had a look at the drawings of the new cathedral centre, and also arranged to come with me to Gobabis the next time I go there. Then I went to see Penny Whitford to arrange the hymns for the service tomorrow, and went home and went to bed early.

_______________

Writing the letter to the magistrate at Okahandja was, I suppose, “provocation” of a kind. I wanted to provoke them into prosecuting me for entering Ovitoto without a permit, because I thought I had a rock-solid defence — that the law that they said demanded a permit demanded no such thing, and that no permit was needed to enter Ovitoto and return the same day. I thought that the waste of taxpayers money in all these bureaucratic machinations in a conspiracy to stop one sick old lady from receiving communion needed to be exposed. And also that government officials, like the reserve superintendent and the magistrate, were exceeding their authority.

The Attorney General had declined to prosecute, it is clear, because he knew the law, and knew that a prosecution would never succeed. The way the SB reports are worded suggests that they were dropping hints to the Minister of Justice that the Attorney General was politically unreliable, and that he needed to be replaced by a more compliant one. I wonder if he was transferred as a result.

One interesting part of the SB reports quoted above has nothing to do with Ovitoto:

“During the student riots (onluste) in the north of S.W.A. there were regular reports of HAYES involvement in the organisation and development of events.”

I wonder where those “regular reports” emanated from, or if it was just something that the SB had sucked out of their thumbs.

The only thing I had done was to phone Toni Halberstadt (who was then teaching at the Anglican school in Odibo) to ask for news about the boycott of the opening of the recently-nationalised Ongwediva College, which Clive Cowley, the editor of the Windhoek Advertiser, was eager to publish, since he had been refused a permit to attend that event, which he had been informed of beforehand by a gloating Kurt Dahlmann, the editor of the sister paper, the Allgemeine Zeitung.

So there was this huge bureaucratic tizz, which involved correspondence and memos going back and forth between the Reserve Superintendent of Ovitoto, the Magistrate at Okahandja, the Department of Bantu Administration and Development in Windhoek (and probably Pretoria as well), the Security Police in Windhoek and Pretoria, the Commissioner of Police (KOMPOL — a nice Soviet-style acronym) in Pretoria, and the Secretary and Minister of Justice, all at the taxpayers’ expense. And all of it aimed at stopping one sick old lady from receiving Holy Communion before she died.

It was altogether banal. And altogether evil.

Notes and references

[1] There is a description of the funeral of Aletta Tooromba, with pictures, here.

[2] Hiskia Uanivi was then a student at the Lutheran Seminary at Otjimbingue, and was spending part of his vacation in Windhoek.

[3] John and Jenny Aitchison lived in Pietermaritzburg. John had been a close friend when I was at university. He married my cousin Jennifer Growdon and later became Professor of Education at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. At the time of these events we produced a small Christian magazine called Ikon, which had to cease publication when all the editors were banned by the government.

Tales from Dystopia is a series of posts I am doing at irregular intervals, with memories of the apartheid era. Some of my fellow South African bloggers said that we should not forget what happened in our past, so that we can learn the lessons of history. So these posts are my contribution to that.

nice to read again a quotation featuring Hannah Arendt …

Thank you for this, Steve. it is very moving. And, as you say, very illustrative of the banality of evil. I think it is important to remember those times. One day, there might be apartheid-deniers in the same way as there are currently Holocaust-deniers. And those of us who have never lived through times like that need an understanding and an appreciation of how people who resisted tyranny in the way that you did, so that if it ever happens again, we know how to resist.

And I also associate the bit about Weston in Perelandra with the phrase ‘the banality of evil’. I wonder if Lewis intended that?

Thanks for the kind comments. Though all this does, of course, go against the idea of “separation of church and state” 🙂

Hi Mr. Hayes,

This was indeed an interesting read and very much educative. I was raised in the very same small village (Oruua – Ovitoto) during the early 80’s and know the referred to families quite well, quite unfortunate that I never got to know the said Aletta Tooromba though heard about her, but I personally know Uncle Mateus, Magdalena and her sisters and mother (who passed away in the early 90’s). Its worth the mention that now in an independent state that a few things have indeed changed and a bit of modernization is slowly but surely setting in, the roads are much better now (reachable with a sedan) and there is electricity in some areas.

In some cases in my thoughts i would wonder how our people got to hear of the Gospel especially for those that never went to the City but now at least part of that inquisition has an answer to it.

A big Thank you for this blog and if you have to visit the area again you surely won’t run into a certain “Mr. Pretorius” let alone need a permit (LOL – humour). All the best.

Thanks very much for the news of people I knew, and if you run into anyone I knew, please give them my greetings and love.